Dear Partner,

For almost 25 years now, I have used an investment process that focuses on normalized earnings and free cash flow as determinants of business value. The fair value of a business generally evolves slowly over years while stock prices can vary widely from day to day. In the short term, the volatility of prices relative to the stability of underlying value creates opportunities to buy stocks when they are trading at a substantial discount to our assessment of intrinsic value and to sell them after that gap has closed.

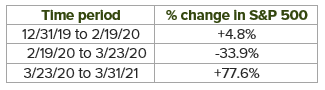

Intellectually, it’s a fairly simple and straightforward process; in practice, it is far harder. I fell in love with the “treasure hunting” aspect of investing when I was in high school and that challenge continues to fuel me to this day. As I reflect back on the returns generated from my bottom-up stock picking, I can’t help but notice that results are dramatically influenced by prevailing investor attitudes; while I keep doing the same thing, day in and day out, the collective “wisdom” of market participants is anything but stable. For example, in the last 15 months, changes in stock prices (as represented by the S&P 500) simply can’t be explained by changes in long-term business fundamentals:

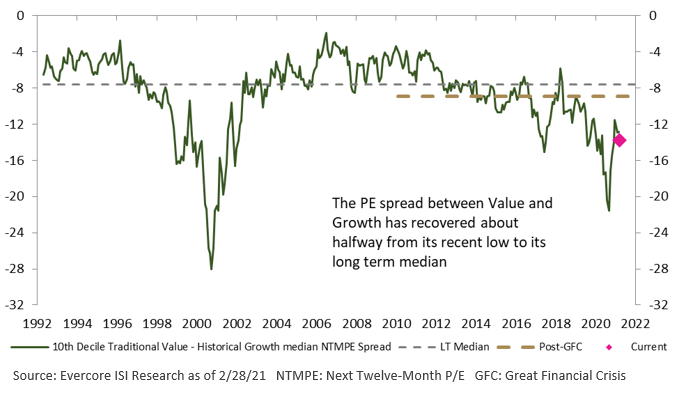

During these wild market swings, we’ve seen a marked change in the type of companies that investors favor. Former growth darlings are being sold to free up funds to purchase shares of economically-sensitive businesses. Investors want beneficiaries of economic reopening and reflation driven by vaccine deployment and continued fiscal and monetary stimulus. As a result, value stocks have begun to materially outperform growth stocks. I believe this change in market leadership signals the beginning of a multi-year period of outperformance as value stocks deliver the competitive earnings growth needed to narrow the historically wide valuation gap between growth and value stocks.

Despite Poplar Forest’s recent positive investment results, our portfolio is still valued at just 60% of the S&P 500’s P/E ratio. In short, our portfolio appears to be attractively valued on an absolute basis and even more so relative to a stock market sitting near all-time high levels. With economic growth accelerating, we believe our companies can grow earnings at a very attractive rate that is not reflected in a 13x P/E on consensus 2021 earnings estimates – estimates that we believe will prove too low. Our portfolio also has a 5.5% free cash flow yield (latest 12 months) and we believe that free cash flow can grow 9-10% per year for at least the next three to four years.

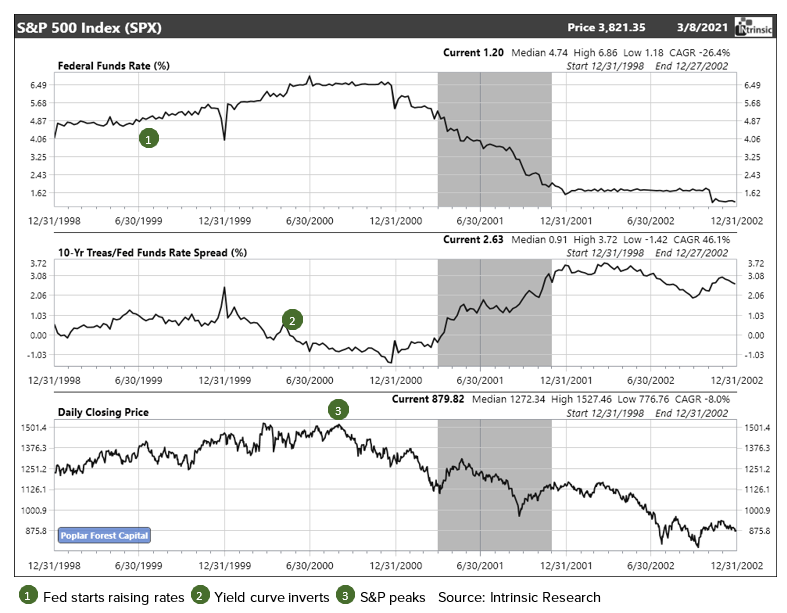

Some investors worry that rising interest rates will derail the bull market that started in the depths of the COVID crisis. While rising rates may well be a headwind for the most expensively valued stocks, increasing long-term interest rates are a signal that the economy is recovering – and that should be good for value stocks. Historically, interest rates haven’t been a problem for the market until the yield curve inverts (when short-term interest rates are higher than long-term rates). In recent months, long-term interest rates have increased while short-term rates have stayed pinned down by the Fed – the curve has steepened. A steepening curve is a sign that markets are growing increasingly confident that stimulus plus vaccines will lead to a progressively stronger economy. This is a fundamentally bullish outlook for the stocks we own.

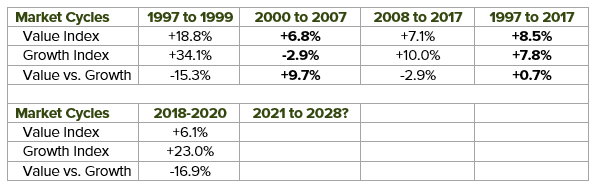

When contemplating value stocks’ prospects, I think a review of the past can help us as we look to the future. While every market cycle has its own unique characteristics, I continue to see many parallels between the last few years and the late 1990s when I first started managing money in the American Balanced Fund. If the next few years bear any resemblance to the period following the tech bubble, then the strategies we employ at Poplar Forest could be particularly timely. While the pages that follow may be a bit nerdy, I found it useful to delve into the past few market cycles I’ve lived through as a way of framing what the future may hold for value investing.

1997-1999 – Inflating of the “Tech” Bubble – Goliath Dominates

While much attention was given to speculation in tech stocks in the late 1990s, the bubble extended well beyond the tech sector. Yes, Microsoft and Cisco were valued at more than 70x earnings, but it didn’t stop there. More prosaic but large companies, like General Electric and Wal-Mart, traded at more than 45x earnings. In that way, the “tech” bubble was reminiscent of the Nifty 50 era of the 1960s when a small subset of companies was deemed to be dominant and unassailable, and therefore worthy of exorbitantly rich valuation premiums relative to their peers.

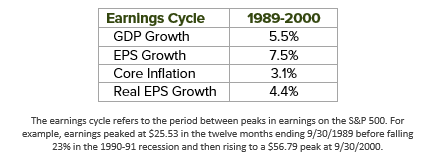

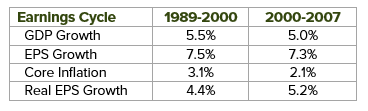

During the inflating of the “tech” bubble, the Russell 1000 Growth Index beat the Russell 1000 Value Index by more than 15% a year for three years. This period of capital-spending-led ebullience was the culmination of an 11-year expansion that saw the S&P grow earnings by 7.5% per year.

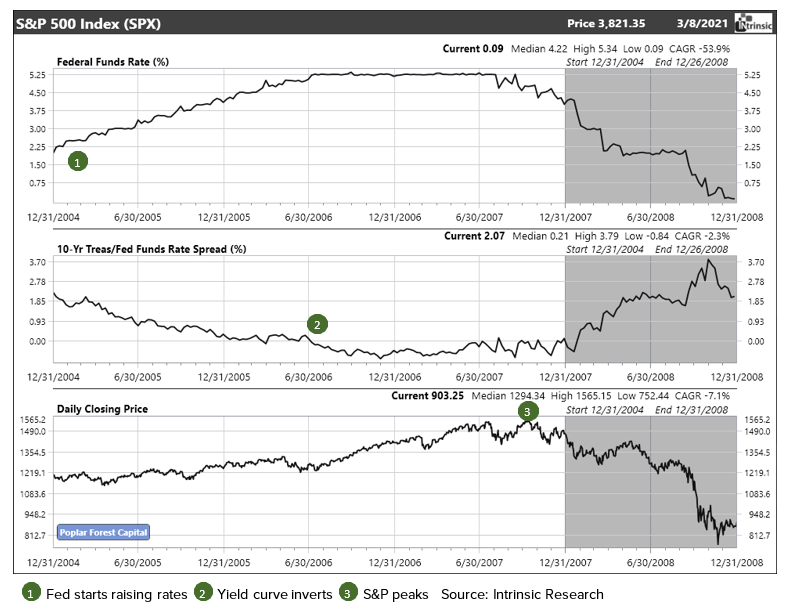

Given the economic exuberance experienced during the “tech” bubble, it was no surprise to see the Federal Reserve raise interest rates in mid-1999. As was historically typical, the market peaked not long after the yield curve inverted (10-year Treasury yields lower than Fed Funds) about nine months later. For those less involved in investing day-to-day, the yield curve is a representation of the interest rates (yields) on similar quality bonds of different maturities. For example, it could refer to the difference in interest rates of a 10-year Treasury bond relative to the short-term interest rate targeted by the Federal Reserve (so called “Fed Funds”).

2000-2007 – Value Rebound – Goliath Loses to David

When the tech bubble burst, the economy went into a shallow recession that saw a 32% decline in earnings for the S&P 500. The Fed cut interest rates to fight the recession. As it turned out, the “unassailable” market leaders weren’t as bullet proof as expected and the underdog “old economy” stocks held up well. As the bubble deflated (from 2000 to 2002), the Value Index beat the Growth Index by 18.5% per year – enough to recover the prior three years’ underperformance and then some. Value stocks continued to perform well in the recovery and, by the end of 2006, the Russell 1000 Value Index had outperformed its Growth counterpart for seven years in a row.

While this economic expansion didn’t last as long as its predecessor, underlying market fundamentals were similar:

A housing market fueled by low interest rates became overheated and, as was typical of past cycles, the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates to combat fears of inflation. As in the late 1990s, the yield curve inverted before the stock market peaked.

2008-2019 – Tepid Recovery from Financial Crisis – followed by a 1990s’ Redux

As has been well documented, the aftermath of the bursting of the housing bubble was much more systemically challenging than was the recovery from the capital spending slump that followed the popping of the “tech” bubble. Earnings for companies in the S&P 500 fell by 57% and it took four years for them to recover to their 2007 peak. Earnings took another hit in the 2015 “Industrial Recession,” but the pain was contained to companies that made stuff and the overall economy moved forward.

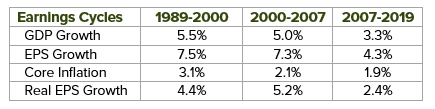

Ultimately, the Trump tax cuts in 2017 led to a renewed burst of activity, yet the resulting economic recovery still paled in comparison to past expansions:

Given the tepid recovery after the Global Financial Crisis, companies that did have solid growth started to see inflation in their valuation – a so-called growth scarcity premium – and the Russell Growth Index beat the Value Index by about 3% a year from 2008-2016. As we saw in the late 1990s, a subset of these companies was subsequently anointed as incontrovertible winners in what are perceived to be winner-take-all markets. Valuation metrics expanded and though the language was slightly different, we saw a 1990s redux of “Old” versus “New” economy stocks. The Growth Index trounced the Value Index by 16.9% per year for three years (as compared to 15.3% in ’97-’99).

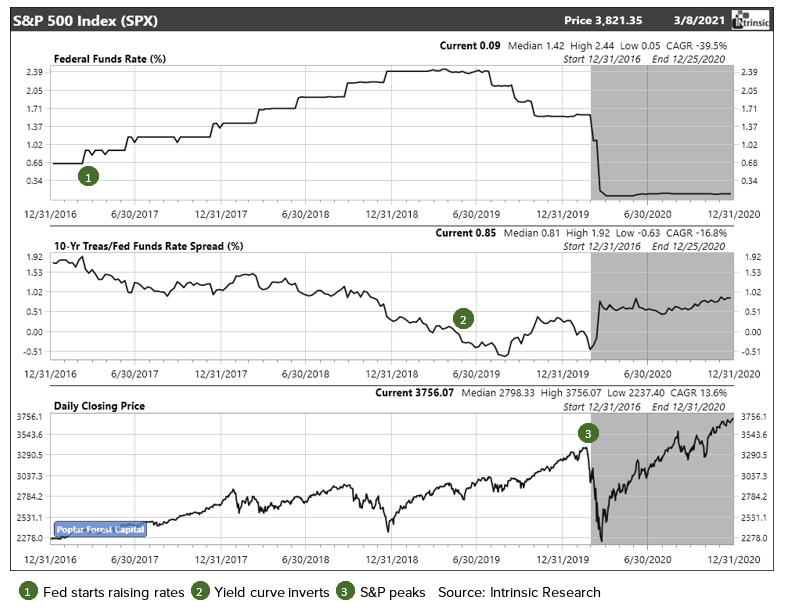

Meanwhile, as economic growth started to accelerate in response to the Trump tax cuts, the Federal Reserve started on a path to “normalize” interest rates. Yet again, the yield curve inverted. While at the time I rationalized away the inversion, given the apparent lack of bubbles in need of popping, history suggested that the stage was set for a bear market. While COVID will be remembered as the cause of the 2020 bear market, I can’t help but wonder if we’d have had to live through a challenging period regardless of our need to be socially distanced for health reasons.

Looking Ahead – Is the Stage Set for a Replay of 2000-2007?

I think the most important observation regarding the current market cycle is that officials from the White House to Congress to the U.S. Treasury to the Federal Reserve are all committed to delivering more robust economic growth than we experienced in the years that followed the Global Financial Crisis. With COVID vaccinations expanding rapidly and unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus, earnings appear set to rebound faster than prior recoveries. With more widespread earnings growth, the so-called “growth scarcity premium” seems likely to continue to dissipate while value stocks enjoy a positive re-rating. If the next eight years follow the same pattern as 2000-2007 (just as 2018-2020 mirrored 1997-1999), then Poplar Forest’s investment program could really shine. If value beats growth, I believe that we can beat both because we run concentrated, high-conviction, benchmark-agnostic portfolios.

Current circumstances – accelerating earnings growth and a wide valuation differential between growth and value stocks – remind me of the early days of the 2000-2007 value cycle. While I’m sure there will be unique characteristics this time around, the situation looks to be full of promise. I’ve used the same investment process for nearly a quarter century, and after comparing the results of that process both at Poplar Forest and at the Capital Group, I strongly believe that the ingredients are in place for several years of rewarding results for the strategies we employ at Poplar Forest!

Sincerely,

J. Dale Harvey

Standardized Performance and Top Ten Holdings: Partners Fund, Cornerstone Fund

Performance data quoted represents past performance; past performance does not guarantee future results. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Current performance of the fund may be lower or higher than the performance quoted. Performance data current to the most recent month end may be obtained by calling 877-522-8860.

Opinions expressed are subject to change at any time, are not guaranteed and should not be considered investment advice. Holdings and allocations are subject to change at any time and should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Index performance is not indicative of a fund’s performance. Value stocks typically are less volatile than growth stocks; however, value stocks have a lower expected growth rate in earnings and sales.