Dear Partner,

I’ve been investing for almost 40 years now, so I’ve lived through many booms and busts, however, I’ve never seen anything quite like the COVID Crash. It took just 20 days for the S&P 500 to fall the 20% required to put us in a bear market. For the first time since 1997, stock market circuit breakers, designed to slow selloffs, were triggered three times in six days. We’ve experienced unprecedented day-to-day volatility: in March, the S&P 500 moved up or down by at least 4% in eight consecutive sessions, eclipsing the old record of six days in 1929. The pace of change is unprecedented.

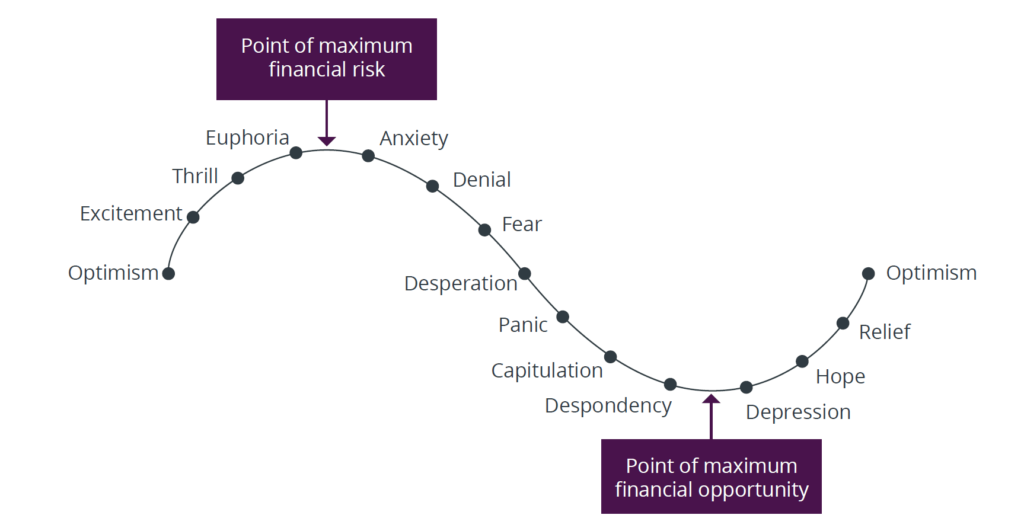

This is the fourth bear market I’ve faced in my investing career. Along the way, there have also been several near bear market declines of 19.3-19.9%. While each selloff had a seemingly scary cause, in every case the market found its way to new highs. Markets are impacted by economic fundamentals, but those fundamentals are often magnified by emotion. While every cycle is different, I believe the graphic below does a very good job of describing investor attitudes.

Cycle of Investor Attitudes:

Understanding where market sentiment lies on this emotional continuum is very helpful in managing portfolios. In the last eight weeks, we’ve gone from fear to panic to capitulation to, as I write this, signs of hope. The period of despondency and depression, usually a time of maximum financial opportunity, lasted just a few days as opposed to the weeks or months of past cycles. It is hard to believe that the worst could be over so soon, but this cycle has certainly been unique.

Understanding where market sentiment lies on this emotional continuum is very helpful in managing portfolios. In the last eight weeks, we’ve gone from fear to panic to capitulation to, as I write this, signs of hope. The period of despondency and depression, usually a time of maximum financial opportunity, lasted just a few days as opposed to the weeks or months of past cycles. It is hard to believe that the worst could be over so soon, but this cycle has certainly been unique.

I’ve learned first-hand that managing through a bear market requires experience, the self-knowledge that comes with it, and the consistent application of a philosophically sound investment process. The first bear market of my career came in 1987, a few months after I had started work as a financial analyst at Morgan Stanley. There had been a boom in merger and acquisition (M&A) activity in those days. Then, seemingly out of the blue, a big deal couldn’t get financing. The M&A bubble started deflating and the market headed lower. Extensive use of “portfolio insurance,” a quantitative risk management tool, magnified the selling. The market plunged 22% in a day. Stories comparing the 1987 experience to the Crash of 1929 were rampant. Many thought we were headed for another depression. I distinctly remember one banker worrying out loud that he was going to get laid off and that his fancy new car was going to be repossessed.

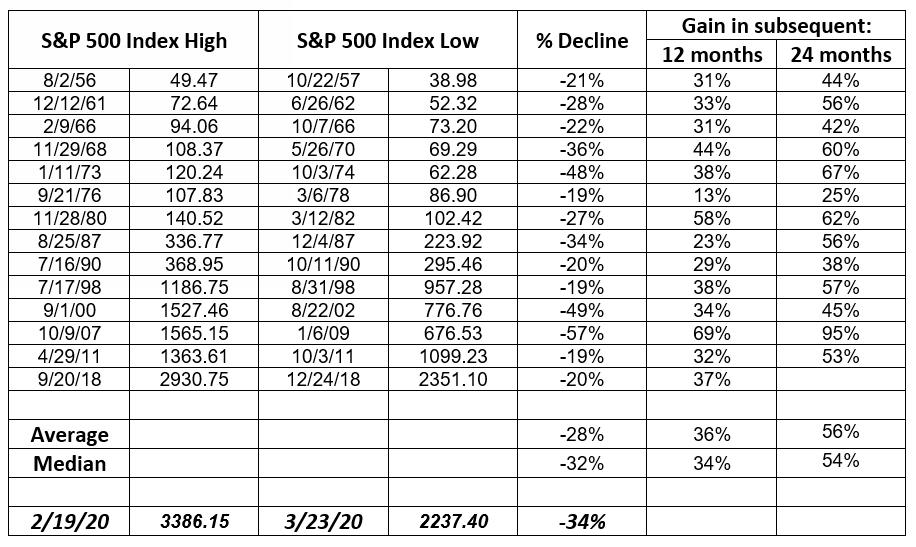

Perhaps I was naive, but I never feared for my job. I’m inherently a “glass-half-full” person, and I saw the selloff as an opportunity to buy. As a newly minted college graduate, I didn’t have ready savings, so I borrowed $10,000 from the savings & loan back home and invested it. The S&P gained 23% in the 12 months after the market bottomed in December 1987. And the gains continued. By December 1989, the market had gained 56% from the low. While I’m not suggesting that anyone lever up for investment purposes today, even after paying an 8% interest rate on my loan, my decision to borrow money to buy stocks in the ’87 Crash paid off handsomely in the recovery.

It’s Different This Time

In my experience, every major market selloff has its own unique cause. Moreover, the magnitude and duration of the decline depends largely on where market attitudes were when the selloff began, and by the authorities’ response to the decline. In the case of the COVID Crash, I’m hopeful that we’ve seen the low for this cycle (down 34%). The starting point was, on the Investor Attitudes Spectrum, more a time of Optimism, than dangerous Euphoria. Furthermore, the lessons of 2000 and 2007 have pushed government authorities to act quickly and expansively this time around. While money can’t cure illness, it can lessen the impact of illness on the economy.

From an analytical point of view, the COVID Crash is challenging in that we are dealing with a pandemic that seems straight out of the pages of a Stephen King novel. “Social distancing” is now part of the collective vernacular as we try to slow the spread of the disease by closing schools, working remotely, eating at home, and canceling concerts and sporting events. The closest corollary to the current crisis is the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918-19, but no one active in markets today was alive then. Interestingly, the stock market shrugged off the Spanish Flu pandemic, though afterwards, once the virus had run its course, the market rallied 50% between February and November 1919.

Even though COVID-19 is technically a beta coronavirus like SARS (2003) or MERS (2012), its impact has been far greater since asymptomatic carriers can spread the virus unknowingly. Experts believe that eventually, social distancing will beat back the virus, but none of us know whether that will take two weeks or six months. Warm weather may help, or it may not. As always, uncertainty adds risk to the investment decision making process, but the feeling of “not knowing” this time around has felt particularly acute.

Here’s how that played out in the market: In late February, investors started selling stocks because they were worried about how the virus would spread. Apprehension was further magnified by an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, the likes of which we haven’t seen since 1986. As the number of anxious sellers increased, the number of willing buyers decreased. The only way to settle the books is price and, as we’ve seen, it took big markdowns to entice wary buyers to step into the breach created by the virus. This re-pricing was further aggravated by the current structure of our investment markets, particularly the size of passive investment products like index funds and ETFs. These passive products buy a little of everything when new money comes in and they sell a little of everything when clients want their money back. This valuation-insensitive selling and buying has been clearly evident in daily trading. And like portfolio insurance in 1987, today’s algorithmic risk management systems equate increasing volatility with risk. The models are designed to sell stocks when volatility increases and to buy when volatility is low. This can have the unintended consequence of creating a feedback loop that amplifies the market’s decline and recovery.

History Doesn’t Repeat, but it Often Rhymes

By the end of February, it became clear that COVID-19 was following a different path than either SARS or MERS. In response, our investment team started meeting every morning to review the latest news on the disease and its impact on the economy and on the companies in which we’re invested. We’ve paid extra attention to the financial liquidity of our companies; investing is a marathon and we want to ensure they all finish the race. Financial strength has always been a component of our investment process and we entered this crisis with just three investments that had a less than investment grade debt rating. Our exposure to these companies totalled about 7% of our assets – well below our 15% internal guideline.

Based on our research, we believe the illness will likely be with us in some form for months, and we expect the impact of social distancing to create a nasty 2020 recession. That said, recent dramatic price declines are offering us opportunities to buy good businesses that we’d be happy to own through a recession and for years to come. While we are working longer hours each day as we sort through the flood of coronavirus information and review dramatically changing stock prices, we are excited to be on what feels like a massive treasure hunt. As other investors sell due to short-term fear, we are buying at prices that we believe will look exceedingly attractive with the benefit of hindsight.

The stock market is a discounting mechanism that looks to the future. In the past, the typical S&P 500 low has preceded economic recovery by about four months. This leads me to believe that the stock market is likely to bottom and then turn higher before the economy reaches its nadir. Those who wait to buy until they’ve gotten an “all clear” message from economists or medical professionals could end up paying a hefty certainty tax in the form of much higher stock prices.

Given all the volatility, we have been a bit more active in the portfolio lately and we are currently invested in a slightly longer list of investments than is typical for us. Tactically, we have been placing smaller orders than normal and we are being very price sensitive. At the individual stock level, we are paying more attention to relative price action than we have historically. Generally, we’ve let our winners run, though we cut back a couple positions that breached the 6.5% of assets threshold. We have done and will continue to do some tax loss harvesting. Given this approach, portfolio turnover is running a bit higher than usual. Cash and equivalents are currently around 3% of our portfolios – own from 5-6% at the start of the year.

At the macro level, we are watching interest rates, credit spreads, oil prices and stock price volatility closely as we look for confirmation signs of a market bottom. We are also watching stock price trends and looking for patterns that are reminiscent of past investment cycles. As you can see below, since 1952 there have been 14 declines of at least 19.3%. While I recognize that most market observers use 20% as the threshold for a bear market, I think it’s instructive to include the five near bear market declines of 19-20% (1976, 1990, 1998, 2011 and 2018) in an examination of market selloffs.

As you can see above, the current decline is in the middle of the pack relative to the biggest market selloffs since 1952. You might also notice that the gains following a low in the market are substantial: roughly 35% after a year and over 50% over two years. Potential buying opportunities like this don’t come around that often. And with the cheapest (“deep value”) stocks in the market having been particularly punished in the COVID Crash, it may come as no surprise that our portfolio is currently valued at less than 7x consensus earnings estimates for 2020. While the full impact of the virus-induced recession isn’t reflected in those estimates, even a 20% revision in earnings would put the portfolio at roughly 8.5x earnings – far cheaper than our portfolio during the financial crisis in 2008-09.

When you look more closely at the details of past bear and near bear markets, what you find is a pattern of a large initial decline, a rally that typically recaptures 30-35% of the loss, followed by a second decline (a “test” of the low). Said another way, the market almost never makes a “V” bottom; the pattern looks more like a “W.” Importantly, this means we don’t have to rush to deploy all of our cash today because the market is likely to give us a second chance to buy. We have used the first phase of the current selloff to establish several small new positions while liquidating one investment (Devon Energy). Assuming past patterns hold, we will likely look to add to these new investments when the market “tests the low” – provided that we continue to have confidence in each company’s outlook and that their respective stock prices are at levels that we find attractive. That said, given all the volatility, we may find even better bargains to add to in coming weeks/months.

Looking Forward

As we look ahead, we are closely watching the rate of growth in new coronavirus cases. We believe we will see a peak in the next four to eight weeks. In addition, the emergence of effective treatment protocols in the coming weeks and months will be key to improving investor sentiment and to hastening the stock market’s recovery. Multiple therapies are currently being studied and, as reporting of trial data continues, we are confident that research teams will soon report good news.

Central banks around the world are providing massive amounts of monetary stimulus. Governments have joined in the rescue mission through aggressive new fiscal spending programs. Together, these actions should help minimize the economic impact of the pandemic and prime the pump for what could be a robust recovery once life returns to something resembling “normal” in the fourth quarter and beyond, provided we don’t get a second wave of virus in fall/winter. It is important to remember that the U.S. economy was on an improving trend in advance of the virus. We’d gotten a partial truce in the trade war and the Fed’s July 2019 rate cut appeared to be having its desired effect. The Manufacturing PMI had turned higher. Unemployment was historically low. Furthermore, our banking system was well capitalized and will likely be a help in this crisis (in sharp contrast to the last crisis, in 2008-09, when it was at the epicenter).

I can’t say for certain that we’ve seen the worst of the COVID Crash, but the March selloff has all the signs of Capitulation that I’ve seen near other major market lows. My experience and familiarity with market history provide a framework for managing through this bear market. While others panic and fret over uncertain short-term news flow, the Poplar Forest team will stick to its discipline of focusing on normalized, long-term earnings and free cash flow. I believe brighter days are coming and that there will be handsome rewards for those who can remain calm in the midst of panic.

Stay safe and healthy, and please reach out if you have any questions that we might answer,

Sincerely,

J. Dale Harvey

Standardized Performance and Top Ten Holdings: Partners Fund, Cornerstone Fund

Performance data quoted represents past performance; past performance does not guarantee future results. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Current performance of the fund may be lower or higher than the performance quoted. Performance data current to the most recent month end may be obtained by calling 877-522-8860.

Opinions expressed are subject to change at any time, are not guaranteed and should not be considered investment advice. Holdings and allocations are subject to change at any time and should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Index performance is not indicative of a fund’s performance. Value stocks typically are less volatile than growth stocks; however, value stocks have a lower expected growth rate in earnings and sales.